Hidden in Plain Sight

Immanuel Mission Church, Kent Co., DE

Indian Mission Church, Sussex Co., DE

St. John Church, Cumberland Co., NJ

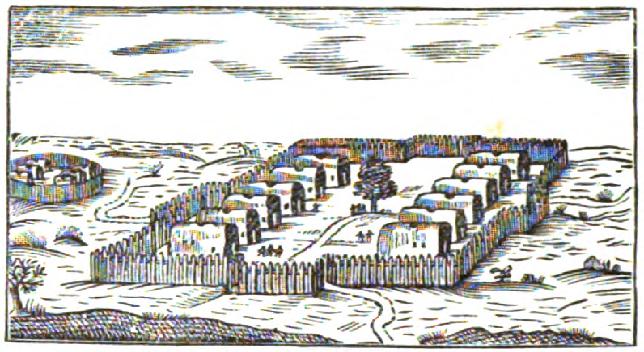

By 1800, the majority of those in the tribal communities had been converted to Christianity, while still maintaining many traditional Nanticoke and Lenape spiritual values. Each of our three interrelated Nanticoke and Lenape tribal communities sustained their internal governance through tribal congregations. Through the 1800’s and 1900’s, tribal control over the congregations was fiercely guarded by each tribal community, sometimes putting them at odds with denominational leadership…

…We have our own church buildings and government… Others may come as often as they choose and are quite welcome and a good many do come, but no strangers are admitted to membership or can have any voice in the management. A number of years ago the Methodist Conference succeeded in taking one of our churches from us, down in Sussex, but our people immediately built another for themselves and connected themselves with the Methodist Protestants. That is why we want no strangers to join our church here; that occurrence was a lesson to us.” (John Sanders, a Kent County tribal elder, in an 1892 article published in The Times of Philadelphia)

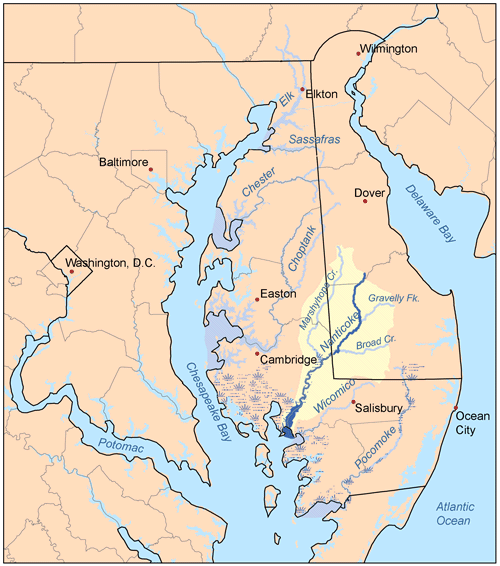

Tribal churches in Cumberland County (New Jersey), Kent and Sussex Counties (Delaware) have all been documented and acknowledged as Historic American Indian Congregations.

Nanticoke and Lenape School Children c.1942

Nanticoke School Children c.1915

In Kent and Sussex Counties, Delaware, tribally controlled segregated schools were established by the communities in the mid to late 1800’s and continued as Native American public schools, with tribal school boards, into the mid 1900’s. The issue of tribal education resulting in an 1881 Delaware statute that listed tribal leaders in Sussex County, Delaware. Public support for tribally controlled segregated schools in Kent and Sussex Counties is well documented in state statutes and reports.

Social organizations, exclusive to tribal people, rose within the tribal communities.

In spite of the government effort to eradicate American Indian identity through racial persecution and intentional misidentification in New Jersey and Delaware, from the 1750’s on, public records continued to identify our ancestors and report on our communities. Lists of our tribal families are compiled in government documents, statutes, research reports, and studies from the 1880’s through to the modern era.